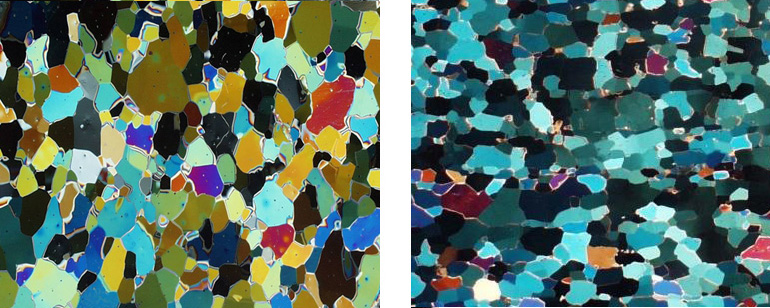

Glaciers are continually changing as temperatures change with seasons and decades, and with gravity the weight of the ice itself forces a flow. Glacier ice crystals are a different shape from other ice because of the pressures exerted upon them – they begin with the usual hexagonal plates, and then they clump together more and more to form larger crystals, and over time and deeper down they align themselves so the grain of the crystals align with the direction of the glacial flow. Ice is solid, ice changes shape, ice flows.

(The image on left is of new glacier ice, colors representing different directions of crystal structure. The image on the right shows older glacier ice, where the ice crystals have begun to align their direction with the flow of ice.)

Glaciers are a beautiful expression of the liquidity of a solid, and many rocks show the apparent solidity of a (former) liquid. Both are examples of the way the earth is in continual change. Glaciers grind down rocks and move rocks, and the rocks shape and guide the flow of glaciers. We are also made of molecular structures and processes. Our own form is continually changing.

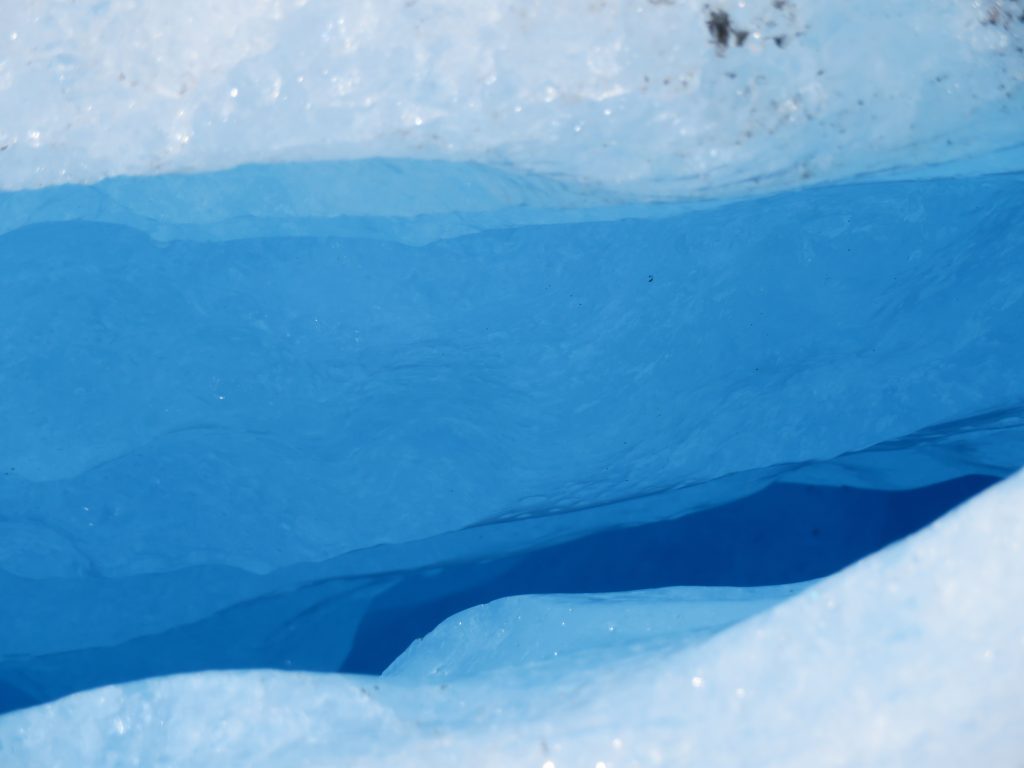

To walk on a glacier is to be in a magical in-between place, a slow motion river – crunchy, slushy on top (on a sunny day) and solid ice below. We could hear the glacier melting deep inside, underfoot. We couldn’t precisely feel it flowing, but we saw changes in the toe of the glacier from our morning outset and our evening departure – a hunk of ice broke off, leaving a dark cave in the ice.

In ‘Glacier Ice’, by Austin Post and Edward R. Lachapelle, there are photographs and words to describe the details and features of glaciers – 79 words are defined in the book: eg., ‘firn’ (snow in the state of transition to glacier ice), ‘nieve penitentes’ (a field of snow or firn pillars produced by an advanced stage of ‘sun cup’ development), ‘tarn’ (a small lake occupying a hollow eroded by glacial erosion) – the language itself is a wonderland – often from nordic languages – from people who live with the active ice world.

The body offers up some tangential correlations: the cerebrospinal fluid cisterns in the brain are called ventricals. Chasms of ice, filled with meltwater, reminded me of the ventricals in the brain; the constant trickle of water within the ice was like the quiet and continuous flow of the cerebrospinal fluid.

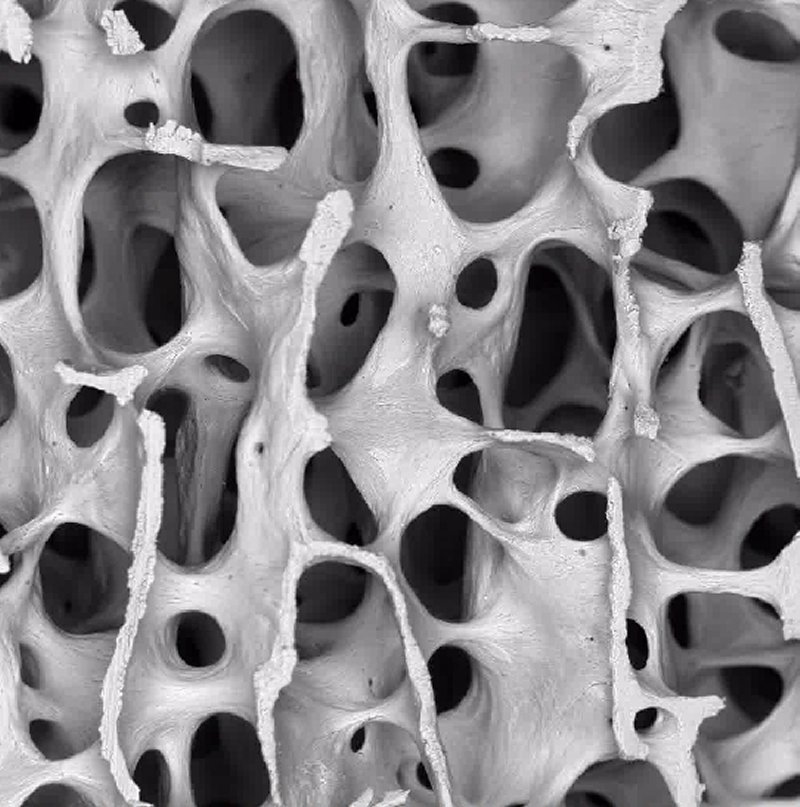

Digging my fingers into the melting surface of the glacier revealed a network of tiny holes, leaving a structural lattice of ice. This reminded me of trabecular bone, the lattice-work of bone at the ends of the long limbs bones. Bone is a tissue whose crystalline structure continually re-forms itself, with ongoing breakdown and building up. Bones, like glaciers, can change shape in response to the forces exerted upon them. The ‘trabecular ice’ (my term) was a result of the way glacial ice is formed, via pressure, to create a more dense, compact set of crystals. This ends up trapping myriad tiny air bubbles. During ice melt, those bubbles emerge and make crackling, popping sounds – (that Cheryl recorded with her underwater mic.) These air pockets also grow and connect as the ice melts, leaving an ice lattice – so a person can dig her fingers into the ice, until the fingers go numb. Probing a glacier felt intimate, like grasping hold of the beast.

(Trabecular bone)

Glaciers are batteries. Receding glaciers in the Andes are devastating for local communities – because they provide a steady water supply. This continual stream feeds all the downstream ecosystems. But glaciers also store energy – they are cold storage – and this becomes important for global climate balance. We think of heat as energy and cold as lack of energy, but for simplicity’s sake, the storage of cold holds potential. Once this is released, then a chain of action happens, and that potential is dissipated, gone.

(A

(This is a model of the Jostedalsbreen glacier – largest glacier in continental Europe. We hiked up one little finger of this, called Nigardsbreen. The model makes clear the dramatic terrain of Norway and the dominant presence of the glacier and its relationship to the fjords, and the countryside between.)

Returning to the body – our window on the world – snow and ice in the environment teach the body to generate energy. Our bodies respond to cold environments with vigor. People who live in snow and ice are able to withstand temperature extremes and to thrive in harsh conditions. We need sun, but we also need vitality-inducing deep cold.

Cheryl and I both have an attraction to snow and ice, and particularly to glaciers. We intend to create a performance piece that is inspired by our direct experience and the raw sounds and images gathered from glaciers. It’s a pilgrimage. We can’t stop the incessant retreat of glaciers. But we can bear witness to the larger-than-life presence of these rivers of ice. The experience changes us, and perhaps in that there is something that will change our actions, and maybe we can influence and inspire others – only by beauty. We are touched by beauty and make art as a translation, running that direct experience through us to create something else – a note scratched into a piece of bark, a shout across a lake. I wouldn’t want to not say anything.

Comments: Add a Comment